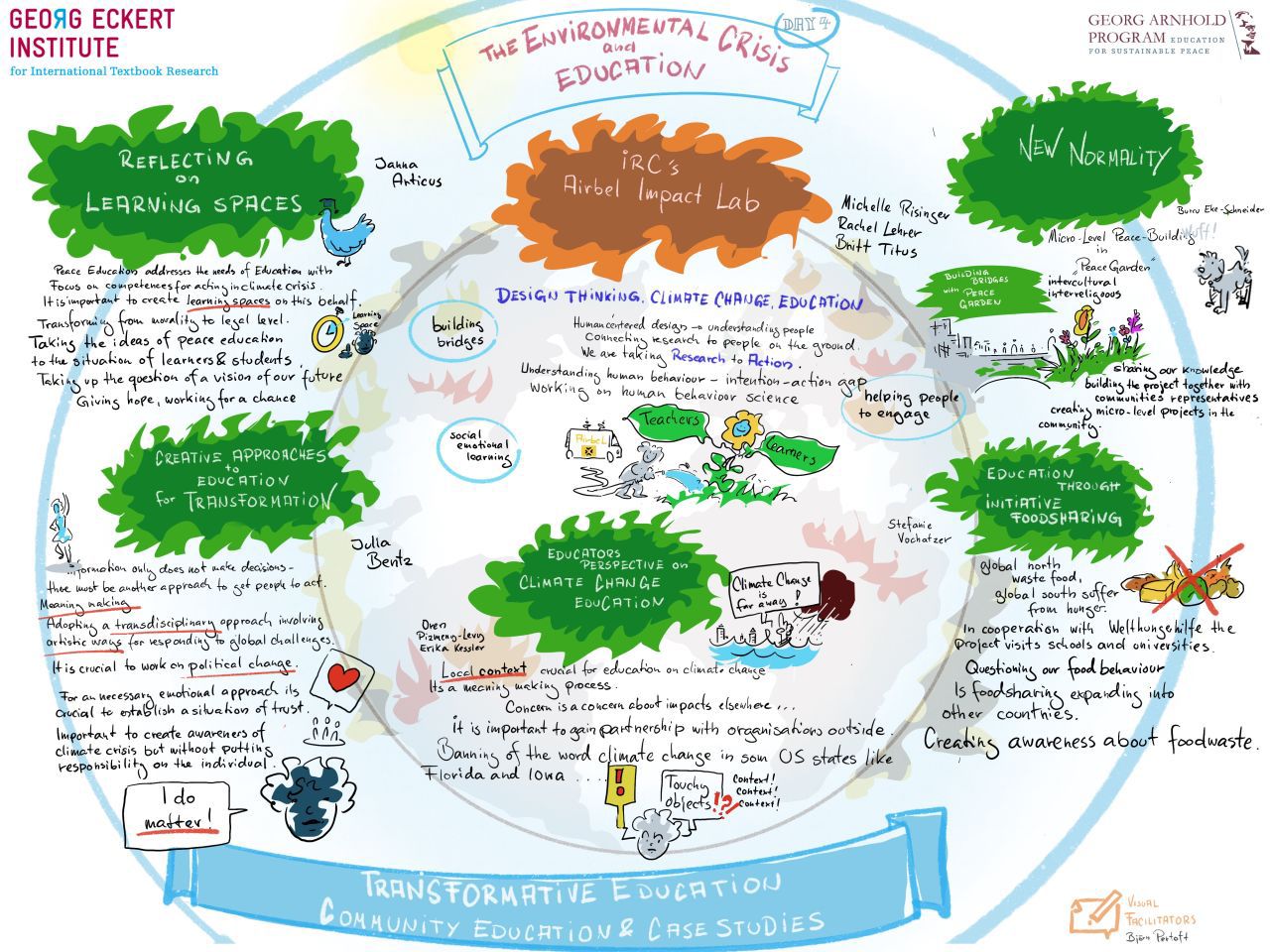

This story has been published by the Georg Eckert Institute’s Leibniz Institute for Educational Media, Georg Arnhold Program internationally as a new method of sustainable education.

Creating Peace Gardens

I was born in Ankara. The streets of the neighborhood I lived in were wide capital avenues with linden and chestnut trees surrounding us with their shadows like a roof in summer. In winter, the poplar trees swayed from side to side with their majestic images, touching the sky. These great giants were friends who made it possible to breathe. The trees protected our mental health, embraced the ecosystem, and made our cities more livable.

I fought for the protection of the last trees on a central square in the city of Istanbul in 2013 during the Gezi Park movement. Society’s representatives of politically oppressed, vulnerable groups, and marginalized people who had come out of the ghettos, were starting to join in, and our protest became the sound of the city, seeking a real transformation. We were protesting against the damage done to our souls and bodies by cities made of concrete, and against the oppressive order which neo-liberal politics had brought upon us. It was a non-violent resistance for peace, justice, and for “us”, against an increasingly authoritarian regime. In the following years, segregation in the society increased. At least, the trees are still there.

Following the protests, I was invited to become a student in a newly founded Peace and Conflict Studies MA Program in Istanbul. While writing my Master’s thesis, I moved to the city of Wuppertal in Germany, where more than half of the population has a migrant background. When I arrived, the city was becoming a home to thousands of Syrian friends fleeing the war. Social injustices caused by ghettoization, isolation, and marginalization are very present in the city.

There was hardly any connection made between science and the real-world in scientific transformation literature in Europe at that time. I carried out a conflict analysis which led me to new ideas and scientific solutions for urban transformation on a micro level.

Jens Nordmann

By creating a dialogue with various actors in the city, we implemented a Peace Garden with diverse friends with backgrounds from Bosnia, Czech Republic, Syria and some local representatives of an marginalized Alevi community. All these communities had experienced war, massacre, or the destructive effect of communism. In order to heal the traumas passed down from generation to generation, the idea of creating a peace garden arose. With the help of nature we wanted to reduce violence in the urban environment.

The opening of the Peace Garden in a community center was celebrated in spring 2020. The Peace Garden uses a “nature-based approach” as a new dialogue method for a sustainable and just future in an urban context. All actors involved are able to meet at eye level – a prerequisite for any transformation.

Over time, the Peace Garden became an educational platform for out of school methods, where we exchange knowledge and learn from each other thanks to intercultural and interreligious dialogue, while growing organic vegetables, fruits and herbs, and learning about local biodiversity.

The city suffered severe damage due to climate change in a storm in July 2021. The same year, I witnessed simultaneous forest fires while visiting my family in my hometown. I believe that everything in the world is interconnected. We need to unite for humanity and nature. For all these reasons, the story of the Peace Garden has set out to heal our cities without forgetting the relationship and interconnectedness between humans, as well as between humanity and nature

While putting an end to these lines, the war drums started to play again in Europe. This is not a world we can accept, so we have to invest in peace through all kinds of new methods. This peace story was written with the hope that the cities we live in will turn into spaces where we can grow sunflowers, love and humanity instead of sowing violence.

Burcu Eke-Schneider

Peace worker